Born 1979, lives and works in Zurich and Bern. In 2008 master’s degree in art history, literature studies, and history at the University of Zurich. From 2009 to 2012 design and art promotion associate, Swiss Federal Office of Culture, Bern. From 2012 to 2014 head of administration and projects, Design Center Langenthal. Since 2012 president of the Expert Committee of the Bern Design Foundation. Freelance author and curator since 2014. Head of design promotion at the Swiss Federal Office of Culture since 2018. In 2019 she published together with Mirjam Fischer the catalogue raisonée “Susi & Ueli Berger. Furniture in Dialogue” (Scheidegger und Spiess).

Failure Is Not an Option?

Failure Is Not an Option?

Swiss Design Awards Online

By Yves Mettler, introduction by Anna Niederhäuser & Lucas Uhlmann

Owing to the cancellation of the exhibition and competition in Basel this year as a result of the pandemic situation, the Swiss Design Awards are staging an alternative programme entitled Failure Is Not an Option?, allowing competition finalists and experts in the field of design to share impressions and knowledge on the very particular year we are experiencing. During the week of 14–18 September 2020 the Swiss Design Awards will broadcast conversations and live chat rooms that will be available to read, watch and comment on the blog. Inspired by the 50th anniversay of the failed Apollo 13 Mission and its film adaptation that led to the now famous quote Failure is not an Option, the Swiss Design Awards hope to question the idea of failure as a malfunction, embrace the reassessment that the absence of normality permits, and perhaps even entertain the idea that failure might be a better option. Before presenting you the programme in detail, we invite you to have a fresh look at the dazzling work of the 37 finalists in the competition through Yves Mettler’s Loop.

Owing to the cancellation of the exhibition and competition in Basel this year as a result of the pandemic situation, the Swiss Design Awards are staging an alternative programme entitled Failure Is Not an Option?, allowing competition finalists and experts in the field of design to share impressions and knowledge on the very particular year we are experiencing. The prize money has been distributed evenly among the 37 finalists in recognition of their selection for the second round of the competition and by way of financial support in these trying times, but this programme is an attempt to make up in some way for another thing we have lost because of the prevailing circumstances: the important and stimulating moments of exchange and networking during the exhibition week in Basel.

Nach der Absage der Ausstellung und des Wettbewerbs in Basel aufgrund der aktuellen Pandemie, organisieren die Swiss Design Awards dieses Jahr ein alternatives Onlineprogramm zum Thema Failure Is Not an Option?. Dieses erlaubt den Finalist*innen des Wettbewerbs sowie ExpertInnen aus dem Designbereich, ihre Eindrücke und Erkenntnisse über das sehr spezielle Jahr 2020 miteinander zu teilen. Das Preisgeld wurde zu gleichen Teilen an alle 37 FinalistInnen als Anerkennung ihrer Wahl in die zweite Runde des Wettbewerbs und als finanzielle Unterstützung in dieser schwierigen Zeit verteilt. Das Alternativprogramm ist ein Beitrag, dem Verlust der Momente des anregenden Austauschs, der Begegnungen und der Vernetzung der Ausstellungswoche in Basel etwas entgegenzuwirken.

Les Swiss Design Awards, consécutivement à l’annulation de l’exposition et de la dernière phase du concours à Bâle en raison de la pandémie, ont choisi de maintenir un programme alternatif intitulé Failure Is Not an Option? – permettant aux finalistes du concours et à des expert·e·s du domaine du design de partager leurs connaissances et impressions sur l’année très particulière que nous vivons. L’ensemble des prix a été réparti égalitairement entre les 37 finalistes en reconnaissance de leur sélection pour le deuxième tour du concours et comme soutien financier. Ce programme est dès lors une tentative de contrer si faire se peut l’impossibilité d’avoir ces moments irremplaçables d’échange ou de rencontre qui accompagnent sinon l’exposition à Bâle.

“During the week of 14–18 September 2020 the Swiss Design Awards will broadcast conversations and live chat rooms that will be available to read, watch and comment on the Swiss Design Awards blog.“

«Während der Woche des 14. – 18. September 2020 werden die Swiss Design Awards Gespräche und live Chat Rooms übertragen, welche zum Lesen, Zuschauen und Kommentieren auf dem Swiss Design Awards Blog verfügbar sein werden.»

«La semaine du 14 au 18 septembre 2020, le blog des Swiss Design Awards diffusera un programme de conversations et chat rooms, contenus à visionner, lire et commenter.»

During the week of 14–18 September 2020 the Swiss Design Awards will broadcast conversations and live chat rooms that will be available to read, watch and comment on the Swiss Design Awards blog. In a second stage, this content will be edited and published in a magazine that will be available this autumn in various institutions and bookstores.

Während der Woche des 14.–18. September 2020 werden die Swiss Design Awards Gespräche und live Chat Rooms übertragen, welche zum Lesen, Zuschauen und Kommentieren auf dem Swiss Design Awards Blog verfügbar sein werden. In einem zweiten Schritt werden die in der Septemberwoche entwickelten Inhalte in einer Publikation verarbeitet, die im Herbst in verschiedenen Institutionen und Buchhandlungen erhältlich sein wird.

La semaine du 14 au 18 septembre 2020, le blog des Swiss Design Awards diffusera un programme de conversations et chat rooms, contenus à visionner, lire et commenter. Dans un second temps, cet ensemble d’opinions sera compilé et publié dans un magazine disponible cet automne dans de nombreuses institutions et librairies.

It has now been 50 years since the Apollo 13 mission was supposed to land on the moon. The story of the mission’s failure but the astronauts’ successful return to Earth has been adapted into a film (Ron Howard, 1995) for which the supposedly original quotation was actually written a posteriori. The perspective offered by the historical context of space exploration combined with the current revival of plans to install a permanent human presence on the Moon, means we can turn the quotation into a question for today.

The Swiss Design Awards are currently also confronted with failure, with the impossibility of functioning as normal. Yet all things being equal, could it not be argued that the Apollo mission was, not only in what it failed to achieve but also in where it succeeded, a design issue? Through the wide-ranging Failure Is Not an Option? programme, the Swiss Design Awards aim to question the idea of failure as a malfunction, embrace the reassessment that the absence of normality permits, and perhaps even entertain the idea that failure might be a better option. This endeavour is especially suited to the design (creative economy) sector, as most of its methods are related to the concept of disrupting the state of things to provide some novelty.

50 Jahre sind vergangen, seit die Apollo 13 Mission auf dem Mond hätte landen sollen. Die Geschichte der gescheiterten Mission und der gleichzeitig erfolgreichen Heimkehr der Astronauten wurde in einem Film umgesetzt (Ron Howard, 1995), für den das vermeintliche Originalzitat Failure Is Not an Option tatsächlich a posteriori geschrieben wurde. Der vergangene Apollo-Kontext bietet in Kombination mit den aktuellen Vorhaben einer permanenten, menschlichen Präsenz auf dem Mond die Gelegenheit, das Zitat in eine Frage für unsere Gegenwart umzuwandeln.

Auch die Swiss Design Awards sind derzeit mit einem Misserfolg – namentlich mit der Unmöglichkeit, wie gewöhnlich zu funktionieren – konfrontiert. Doch könnte man nicht auch argumentieren, dass die Apollo-Mission nicht nur in Bezug auf das, was sie nicht erreicht hat, sondern auch in Bezug auf das, was ihr gelungen ist, eine Designfrage war? Durch das breit angelegte Programm Failure Is Not an Option? wollen die Swiss Design Awards die Idee des Scheiterns als Misserfolg in Frage stellen; die Neuorientierung, die das Fehlen von Normalität zulässt, aufgreifen und vielleicht sogar die Idee in Erwägung ziehen, dass ein Scheitern eine bessere Option sein könnte. Dieses Bestreben eignet sich besonders für den Designsektor (Kreativwirtschaft), da die meisten seiner Methoden mit dem Konzept der Erörterung des Stands der Dinge verbunden sind, um etwas Neues zu schaffen.

Il y a cette année 50 ans que la mission Apollo 13 aurait dû se poser sur la Lune. L’histoire de l’échec de cette expédition dont le rapatriement des astronautes est en soi une réussite a été adaptée dans un film (Ron Howard, 1995) pour lequel la citation soi-disant originale aura été rédigée a posteriori. La mise en perspective de l’époque Apollo doublée du renouveau actuel des intentions d’avoir une présence humaine permanente sur la Lune, permet de construire sur cette citation une question d’actualité.

Les Swiss Design Awards sont actuellement confrontés à l’échec de leur fonctionnement normal. Mais la mission Apollo, toute proportion gardée, là où elle a échoué mais aussi dans ce qu’elle a accompli, n’était-elle pas une problématique de design? Avec le programme Failure Is Not an Option?, les Swiss Design Awards espèrent questionner la définition de l’échec comme insuccès, le potentiel qu’offre la réévaluation d’un contexte non-ordinaire et l’idée que l’échec pourrait peut-être même constituer une better option? Cette thématique semble concerner particulièrement le domaine du design (économie créative) par la liaison de ses buts et méthodes à l’idée de pouvoir remodeler l’état des choses pour y actualiser la nouveauté.

“The Swiss Design Awards aim to question the idea of failure as a malfunction, embrace the reassessment that the absence of normality permits, and perhaps even entertain the idea that failure might be a better option.“

«Die Swiss Design Awards wollen die Idee des Scheiterns als Misserfolg in Frage stellen; die Neuorientierung, die das Fehlen von Normalität zulässt, aufgreifen und vielleicht sogar die Idee in Erwägung ziehen, dass ein Scheitern eine bessere Option sein könnte.»

«Les Swiss Design Awards espèrent questionner la définition de l’échec comme insuccès, le potentiel qu’offre la réévaluation d’un contexte non-ordinaire et l'idée que l'échec pourrait peut-être même constituer une better option?»

With this in mind, we look forward to welcoming you on the Swiss Design Awards blog to follow the responses of designers and experts in their fields. But before that we would like to invite you to take another orbit around the dazzling work of the 37 finalists in the competition through Yves Mettler’s Loop, as a launch pad for a journey into terra incognita.

In diesem Sinne freuen wir uns, euch auf dem Blog der Swiss Design Awards begrüssen zu dürfen, um die Antworten von DesignerInnen und ExpertInnen in ihren Gebieten zu entdecken. Doch zuvor möchten wir euch einladen, die spannenden Arbeiten der 37 Finalistinnen des Wettbewerbs noch einmal durch Yves Mettlers Loop als Ausgangspunkt für terra incognita* zu umkreisen.

Chargés de ces questions, nous nous réjouissons de vous accueillir sur le blog des Swiss Design Awards pour y suivre les réactions des designers et expert.e.s du domaine. Mais avant cela, nous aimerions vous inviter à encore orbiter autour des travaux rayonnants des 37 finalistes du concours, grâce au Loop d’Yves Mettler: une plateforme de lancement vers cette terra incognita.

There’s no question that these are eventful times. In this increasingly present world, how are designers embracing change and continuity? The projects and strategies adopted by the Swiss Design Awards 2020 nominees show that work is already in progress.

Take the graphic designers Adeline Mollard, for example: they’ve been devising a new visual identity for each edition of the Bad Bonn Kilbi festival every year since 2005. Taking their cue from the festival’s experimental spirit, they’ve created over time an identity that is unique and recognisable without being fixed. A similar collaboration in experiment is at work between ceramist Ursula Vogel and the restaurant Maison Manesse. Having developed a porcelain collection for the restaurant, Vogel agreed with chef Fabian Spiquel that broken items would be returned to her studio for the damage to be repaired and marked, thus creating a personal history for the place where the tableware lives. There is a parallel here with the upcycling strategy of fashion designer Rafael Kouto, who finds his raw materials in piles of clothes collected by Texaid. Kouto prints them, cuts them up and puts them back together again, thus imbuing them with new life. In so doing, he gives the haute couture imprimatur to an innovative spirit fostered by practices and thrift drawn from his African origins. The exploration of traditional practices and investigation of cultural shifts is also the theme of the “Hoselupf” series by photographer Sabina Bösch. Shot through with empathy and enlivened by a dash of humour, her images show women engaging in “Schwingen”, or Swiss wrestling, debunking the cliché that this sport is a solely male preserve.

In another vein, Lilla Wicky delves into the archives of the Swiss textile industries to revive the memory of craftsmanship — see her collection created together with the Zürcherische Seidenindustrie Gesellschaft. Typographer Julien Mercier teaches his subject on the Master in Computational Arts at Goldsmiths, but at the same time looks for innovation in forms that are all but lost — as with the Oar typeface. Commissioned by the Oxford Artistic & Practice Based Research Platform and optimised for online publication, it is based on lead type characters that were found by divers at the bottom of the Thames in 2014. To give the public at large access to the results of their research and create a sustainable economy, typographers either work closely with digital foundries — Mercier with Optimo, for example — or create their own, as with Out of the Dark Typefaces by the typographer and graphic designer Philippe Herrmann. Lineto is another Swiss-based foundry offering top-of-the-range typefaces. Graphic and web designer Jonathan Hares created version 3.0 of the site, which also includes an ongoing timeline of typography. A further foray into history can be seen in the work of photographer, graphic designer and editor Nicolas Polli, who gathers together ten years of photography from the Images Vevey festival to create The Book of Images. For all his dedication to photography, Polli has no qualms about switching roles to explore and present practitioners in the latest iterations of the medium.

Polli is also the graphic designer behind the book Happiness is the only true emotion, which is based on research by the photographer Clément Lambelet into imaging technology for automatically recognising emotions. Curiously, happiness was the only emotion that the most widely used image processing program was able to identify among the portraits that the artist submitted to it. Happiness may be easy to recognise, but it’s not so easy to find. In his Doomed Paradise project, photographer Tomas Wüthrich offers a thoroughly ambivalent vision of happiness: the outcome of five years spent with a tribe increasingly threatened by deforestation, among whom environmental activist Bruno Manser had taken refuge. Printed on wood-free paper and including tales, songs and ambient sounds, the book is both a record for the tribe of its lost homeland and culture, and a profound reflection on happiness and remoteness.

A similar reflection on near and far can be found in the work of design studio crisp-id, such as their Tabletop Bistrobar collection for the Bern restaurant Casino. Instead of anonymous tableware, the duo have created a robust yet versatile collection with a limited number of pieces made of ceramic sourced from the closest manufacturer to the restaurant. How does the product adapt to the environment? Can it respond and work better with change? That’s the question that typographer David Massara answers with his Ripley research project: his variable font incorporates information from the light detectors that are omnipresent in our digital interfaces so as to automatically optimise legibility on screen. Further on, exploration of the poetic dimension of automation quickly blurs the boundary between art and design. That’s where we find the design duo AATB, with their Phasma lighting system based on an electronic module and their indoor sun dial made by combining a robot arm with an LED light.

More discreet but just as experimental are the Softspaces of textile designer Marie Schumann . Neither furniture nor lighting, her wall hangings nevertheless inhabit and transform space. Hand-made using an experimental technique on machines in Switzerland and the Netherlands, her textiles combine cotton, polyester, Lurex yarn and, more recently, LEDs and optical fibres. Another team of designers who develop their own techniques and tools are Eurostandard. Their combined skills in graphic design and programming enable them to develop digital tools specifically for each commission, as with the visual identity of the multifaceted festival Les Urbaines, while enlarging their own expertise. Durability is also an issue in the world of fashion — for both labels and products. The duo who make up Collective Swallow devise their own launch schedule, viewing each series as an extension of an open ensemble. They back this up with a strong narrative concept, transforming the social experience of eating into a series of apparel, choosing their materials with great care and injecting a dash of humour.

We encounter these qualities once again in the psychedelic illustrations of Luca Schenardi for anything from newspapers and cultural venues to music. Blending the spontaneity of drawing with the mechanical operations of digital technology, Schenardi takes us inside and give us an intimate understanding of the subjects he illustrates. It’s an understanding that manifests itself quite differently in the work of photographer and artistic director Laurence Kubski. Immersing herself in the relationships between humans and animals, Kubski reconstructs with a kind of remote empathy a world that is otherwise inaccessible. Rather than showing us a universe, Kubski chooses instead to interpret a culture. That desire to showcase a culture is also present in the collections of the fashion label After Work Studio. Urbane, cheeky and yet totally uncompromising on quality, the collections of AWS seem to come from the New York City of tomorrow. Also known for her offbeat stagings for the leading fashion magazines, photographer Mathilde Agius embarks on a new, more personal path, portraying Shanghai nightlife through her DJ friends. The young, Geneva-based fashion designer Lora Sonney explores a different approach to a culture that is both urbane and feminine. Inspired by the raw and intimate atmosphere of the soccer locker room, she puts together a women’s sportswear collection that is supple and energetic, and develops an experimental textile mesh for outdoors. Staying outside, industrial designer Michel Charlot has developed a mesh of a very different kind. His Biennale Bench, commissioned by the Fiskars Design Biennale, supplied the basic design for a series being produced by Burri, a modular urban seating system made from an almost transparent metal mesh. Similarly inspired by what is — for now — still one of the main actors in the urban space, namely the automobile, fashion designer Thomas Clément brings the car right up close to the skin. Combining lace and tartan with synthetic resins and hose, the designer points the way to an urban physicality of the future.

The ways in which a land is incarnated in the bodies and language of those who live in it are at the heart of the Medicine Tree project by photographer Lucas Olivet. The title is taken from the metaphor offered up by a local whom he met while examining the resinous black spruce growing next to his dilapidated caravan: “I’ve never seen a tree produce so much medicine. Perhaps it’s crying because of all the poison here.” Like extensions of our own senses, these accounts help us to find meaning in our truly globalised world. In this vein, and commenting on the strangest or most troubling aspects of our planet, the magazine Reportagen works with illustrator Lina Müller, whose images capture the reader’s mind like riddles inscribed in the folds of memory. Similarly fascinated by the relationship between memory and body is fashion designer Luca Xavier Tanner, who launches his career with a collection of upcycled unisex clothing. Tanner takes garments from his own wardrobe and those of his friends and adds folds and frills, reconfiguring the contours of the bodies they clothe.

Photographer Mathias Renner pushes that art of composition to the extreme with his still lifes. His images, created by gathering together everyday objects, are like ideograms challenging our imaginary. The urgency of the present moment may well be found in that challenge, that opening up of the imaginary now. That, at least, is what the strange cabins of designer Stéphane Barbier Bouvet seem to suggest: that we should remain on the lookout for present potentials while opening ourselves up to future functions; work with what we have; and abandon the logic of a project that always puts off until tomorrow the changes that need to be made to the world today. The same approach is adopted by the designer (Martina Huynh with her Basic Income Café, in which two models of universal income are put into practice and discussed collectively. Meanwhile, photographer Marwan Bassiouni exposes the extent to which different “conceptions of the world” are embedded in our present-day reality. His New Dutch Views show the Dutch countryside seen through the windows of mosques, highlighting just how far cultural heterogeneity constructs our everyday environment. One cannot exist without the other; coexistence requires contrasts and playfulness, as with the cut-outs of illustrator Nadine Spengler. Photographer Roger Eberhard reports on divisions that, somewhat ironically, have failed to withstand the passage of time. His Human Territoriality presents 42 landscapes of borders that no longer exist today.

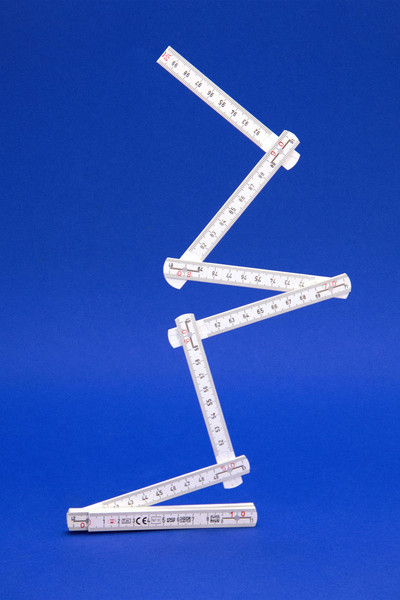

Making things simpler without sacrificing substance is a thankless task, but one that some designers nevertheless embrace enthusiastically. The naive and colourful drawings of Luigi Olivadoti make delicate social subjects accessible, while graphic designer Roger Conscience has spent fifteen years developing the art of diagrams and tables, giving wittily visual form to the most complex data. Deconstruction through design is also at the heart of the book “Cypriot Sketch” by graphic designer Clio Hadjigeorgiou, in which she offers an empirical guide to the ways in which a Cypriot culture is constructed through the appropriations and transformations of the numerous cultures that have passed through the island. On a global scale, that’s also what the research team behind Migrant Journal are trying to achieve, with six meticulously crafted publications that offer an account of a planet essentially defined by movement from place to place.

There’s no question that these are eventful times. In this increasingly present world, how are designers embracing change and continuity? The projects and strategies adopted by the Swiss Design Awards 2020 nominees show that work is already in progress.

Take the graphic designers Adeline Mollard, for example: they’ve been devising a new visual identity for each edition of the Bad Bonn Kilbi festival every year since 2005. Taking their cue from the festival’s experimental spirit, they’ve created over time an identity that is unique and recognisable without being fixed. A similar collaboration in experiment is at work between ceramist Ursula Vogel and the restaurant Maison Manesse. Having developed a porcelain collection for the restaurant, Vogel agreed with chef Fabian Spiquel that broken items would be returned to her studio for the damage to be repaired and marked, thus creating a personal history for the place where the tableware lives. There is a parallel here with the upcycling strategy of fashion designer Rafael Kouto, who finds his raw materials in piles of clothes collected by Texaid. Kouto prints them, cuts them up and puts them back together again, thus imbuing them with new life. In so doing, he gives the haute couture imprimatur to an innovative spirit fostered by practices and thrift drawn from his African origins. The exploration of traditional practices and investigation of cultural shifts is also the theme of the “Hoselupf” series by photographer Sabina Bösch. Shot through with empathy and enlivened by a dash of humour, her images show women engaging in “Schwingen”, or Swiss wrestling, debunking the cliché that this sport is a solely male preserve.

In another vein, Lilla Wicky delves into the archives of the Swiss textile industries to revive the memory of craftsmanship — see her collection created together with the Zürcherische Seidenindustrie Gesellschaft. Typographer Julien Mercier teaches his subject on the Master in Computational Arts at Goldsmiths, but at the same time looks for innovation in forms that are all but lost — as with the Oar typeface. Commissioned by the Oxford Artistic & Practice Based Research Platform and optimised for online publication, it is based on lead type characters that were found by divers at the bottom of the Thames in 2014. To give the public at large access to the results of their research and create a sustainable economy, typographers either work closely with digital foundries — Mercier with Optimo, for example — or create their own, as with Out of the Dark Typefaces by the typographer and graphic designer Philippe Herrmann. Lineto is another Swiss-based foundry offering top-of-the-range typefaces. Graphic and web designer Jonathan Hares created version 3.0 of the site, which also includes an ongoing timeline of typography. A further foray into history can be seen in the work of photographer, graphic designer and editor Nicolas Polli, who gathers together ten years of photography from the Images Vevey festival to create The Book of Images. For all his dedication to photography, Polli has no qualms about switching roles to explore and present practitioners in the latest iterations of the medium.

Polli is also the graphic designer behind the book Happiness is the only true emotion, which is based on research by the photographer Clément Lambelet into imaging technology for automatically recognising emotions. Curiously, happiness was the only emotion that the most widely used image processing program was able to identify among the portraits that the artist submitted to it. Happiness may be easy to recognise, but it’s not so easy to find. In his Doomed Paradise project, photographer Tomas Wüthrich offers a thoroughly ambivalent vision of happiness: the outcome of five years spent with a tribe increasingly threatened by deforestation, among whom environmental activist Bruno Manser had taken refuge. Printed on wood-free paper and including tales, songs and ambient sounds, the book is both a record for the tribe of its lost homeland and culture, and a profound reflection on happiness and remoteness.

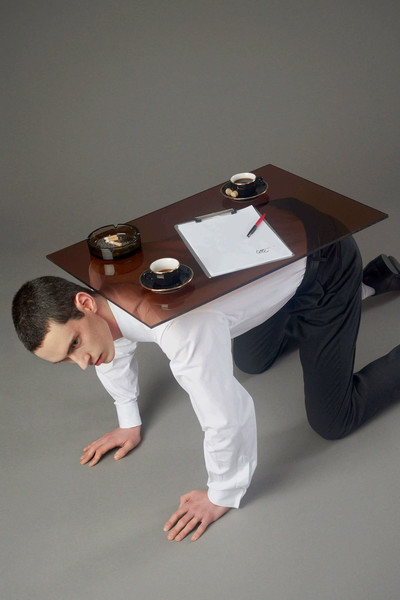

A similar reflection on near and far can be found in the work of design studio crisp-id, such as their Tabletop Bistrobar collection for the Bern restaurant Casino. Instead of anonymous tableware, the duo have created a robust yet versatile collection with a limited number of pieces made of ceramic sourced from the closest manufacturer to the restaurant. How does the product adapt to the environment? Can it respond and work better with change? That’s the question that typographer David Massara answers with his Ripley research project: his variable font incorporates information from the light detectors that are omnipresent in our digital interfaces so as to automatically optimise legibility on screen. Further on, exploration of the poetic dimension of automation quickly blurs the boundary between art and design. That’s where we find the design duo AATB, with their Phasma lighting system based on an electronic module and their indoor sun dial made by combining a robot arm with an LED light.

More discreet but just as experimental are the Softspaces of textile designer Marie Schumann . Neither furniture nor lighting, her wall hangings nevertheless inhabit and transform space. Hand-made using an experimental technique on machines in Switzerland and the Netherlands, her textiles combine cotton, polyester, Lurex yarn and, more recently, LEDs and optical fibres. Another team of designers who develop their own techniques and tools are Eurostandard. Their combined skills in graphic design and programming enable them to develop digital tools specifically for each commission, as with the visual identity of the multifaceted festival Les Urbaines, while enlarging their own expertise. Durability is also an issue in the world of fashion — for both labels and products. The duo who make up Collective Swallow devise their own launch schedule, viewing each series as an extension of an open ensemble. They back this up with a strong narrative concept, transforming the social experience of eating into a series of apparel, choosing their materials with great care and injecting a dash of humour.

We encounter these qualities once again in the psychedelic illustrations of Luca Schenardi for anything from newspapers and cultural venues to music. Blending the spontaneity of drawing with the mechanical operations of digital technology, Schenardi takes us inside and give us an intimate understanding of the subjects he illustrates. It’s an understanding that manifests itself quite differently in the work of photographer and artistic director Laurence Kubski. Immersing herself in the relationships between humans and animals, Kubski reconstructs with a kind of remote empathy a world that is otherwise inaccessible. Rather than showing us a universe, Kubski chooses instead to interpret a culture. That desire to showcase a culture is also present in the collections of the fashion label After Work Studio. Urbane, cheeky and yet totally uncompromising on quality, the collections of AWS seem to come from the New York City of tomorrow. Also known for her offbeat stagings for the leading fashion magazines, photographer Mathilde Agius embarks on a new, more personal path, portraying Shanghai nightlife through her DJ friends. The young, Geneva-based fashion designer Lora Sonney explores a different approach to a culture that is both urbane and feminine. Inspired by the raw and intimate atmosphere of the soccer locker room, she puts together a women’s sportswear collection that is supple and energetic, and develops an experimental textile mesh for outdoors. Staying outside, industrial designer Michel Charlot has developed a mesh of a very different kind. His Biennale Bench, commissioned by the Fiskars Design Biennale, supplied the basic design for a series being produced by Burri, a modular urban seating system made from an almost transparent metal mesh. Similarly inspired by what is — for now — still one of the main actors in the urban space, namely the automobile, fashion designer Thomas Clément brings the car right up close to the skin. Combining lace and tartan with synthetic resins and hose, the designer points the way to an urban physicality of the future.

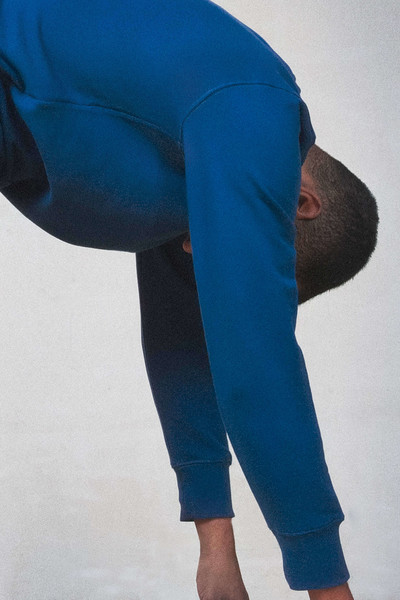

The ways in which a land is incarnated in the bodies and language of those who live in it are at the heart of the Medicine Tree project by photographer Lucas Olivet. The title is taken from the metaphor offered up by a local whom he met while examining the resinous black spruce growing next to his dilapidated caravan: “I’ve never seen a tree produce so much medicine. Perhaps it’s crying because of all the poison here.” Like extensions of our own senses, these accounts help us to find meaning in our truly globalised world. In this vein, and commenting on the strangest or most troubling aspects of our planet, the magazine Reportagen works with illustrator Lina Müller, whose images capture the reader’s mind like riddles inscribed in the folds of memory. Similarly fascinated by the relationship between memory and body is fashion designer Luca Xavier Tanner, who launches his career with a collection of upcycled unisex clothing. Tanner takes garments from his own wardrobe and those of his friends and adds folds and frills, reconfiguring the contours of the bodies they clothe.

Photographer Mathias Renner pushes that art of composition to the extreme with his still lifes. His images, created by gathering together everyday objects, are like ideograms challenging our imaginary. The urgency of the present moment may well be found in that challenge, that opening up of the imaginary now. That, at least, is what the strange cabins of designer Stéphane Barbier Bouvet seem to suggest: that we should remain on the lookout for present potentials while opening ourselves up to future functions; work with what we have; and abandon the logic of a project that always puts off until tomorrow the changes that need to be made to the world today. The same approach is adopted by the designer (Martina Huynh with her Basic Income Café, in which two models of universal income are put into practice and discussed collectively. Meanwhile, photographer Marwan Bassiouni exposes the extent to which different “conceptions of the world” are embedded in our present-day reality. His New Dutch Views show the Dutch countryside seen through the windows of mosques, highlighting just how far cultural heterogeneity constructs our everyday environment. One cannot exist without the other; coexistence requires contrasts and playfulness, as with the cut-outs of illustrator Nadine Spengler. Photographer Roger Eberhard reports on divisions that, somewhat ironically, have failed to withstand the passage of time. His Human Territoriality presents 42 landscapes of borders that no longer exist today.

Making things simpler without sacrificing substance is a thankless task, but one that some designers nevertheless embrace enthusiastically. The naive and colourful drawings of Luigi Olivadoti make delicate social subjects accessible, while graphic designer Roger Conscience has spent fifteen years developing the art of diagrams and tables, giving wittily visual form to the most complex data. Deconstruction through design is also at the heart of the book “Cypriot Sketch” by graphic designer Clio Hadjigeorgiou, in which she offers an empirical guide to the ways in which a Cypriot culture is constructed through the appropriations and transformations of the numerous cultures that have passed through the island. On a global scale, that’s also what the research team behind Migrant Journal are trying to achieve, with six meticulously crafted publications that offer an account of a planet essentially defined by movement from place to place.

Personne ne le contredira, quelque chose se passe aujourd’hui. Dans ce monde toujours plus au présent, comment est-ce que changement et continuité se trouvent intégrés par les designers ? Les projets et les stratégies développés par les nominé-es des Swiss Design Awards 2020 montrent que le travail est déjà en cours.

Il y a par exemple le travail des graphistes Adeline Mollard qui élaborent depuis 2005 une nouvelle identité visuelle pour chaque édition du festival Bad Bonn Kilbi. En travaillant avec l’esprit expérimental du festival, elles créent à la longue une identité unique, reconnaissable sans être fixée. Cette complicité dans l’expérimentation se retrouve aussi dans la collaboration de la céramiste Ursula Vogel et le restaurant Maison Manesse. Après avoir développé une collection de porcelaine pour le restaurant, Vogel et le chef Fabian Spiquel ont décidé que les pièces abîmées passeraient à l’atelier de la céramiste où le dommage sera réparé et marqué, créant ainsi une histoire propre pour le lieu où vit cette vaisselle. Il y a là un parallèle avec la stratégie d’upcycling du fashion designer Rafael Kouto, qui trouve sa matière première dans les piles de vêtements récupérés par Texaid. En imprimant, découpant et remontant ces habits, Kouto leur insuffle une nouvelle vie. Il valorise ainsi dans la Haute Couture un esprit innovatif inspiré par des pratiques et une économie qu’il importe de ses origines africaines. L’exploration des pratiques traditionnelles et rendre compte des déplacements culturels se retrouve dans la série «Hoselupf» de la photographe Sabina Bösch. Ses images présentent avec empathie et une touche d’humour les femmes pratiquants la lutte suisse, le «Schwingen», jetant avec entrain le cliché de l’exclusivité masculine de ce sport aux oubliettes.

Dans l’autre sens, Lilla Wicky, plonge dans les archives des industries textiles suisses pour en extraire la mémoire d’un savoir-faire, comme sa collection créée en collaboration avec la Zürcherische Seidenindustrie Gesellschaft. Le typographe Julien Mercier, bien qu’enseignant en typographie dans le Master de computational Arts de la Goldsmith University, cherche l’innovation dans les formes quasi perdues. C’est le cas de la police de caractère Oar, commandée par l’Oxford Artistic & Practice Based Research Platform et optimisée pour la publication en ligne, qui est basée sur des caractères de plomb trouvée par des plongeurs au fond de la Tamise en 2014. Pour rendre accessible au grand public le résultat de leur recherches et créer une économie durable, les typographes travaillent soit étroitement avec des fonderies digitales, ainsi Mercier avec Optimo, ou crée la leur, comme Out of the Dark Typefaces du typographe et graphiste Philippe Herrmann. Lineto est une autre fonderie basée en Suisse proposant des polices de caractère haut de gamme. Le graphiste et webdesigner Jonathan Hares a créé le design 3.0 du site, offrant entre autre une histoire en cours de la typographie. C’est une autre plongée historique que le photographe, graphiste et éditeur Nicolas Polli rassemble dix ans de photographie à travers le festival Images Vevey dans The Book of Images. Absolument dédié à la photographie, Polli n’hésite pas à changer de fonction pour explorer et présenter les actrices et acteurs des plus récentes mutations de la photographie.

C’est en tant que graphiste que Polli réalise le livre Happiness is the only true emotion, basé sur la recherche du photographe Clément Lambelet autour de l’imagerie pour la reconnaissance automatique des émotions. Étrangement, le bonheur a été seule émotion que le programme de traitement d’image le plus diffusé a su reconnaître avec succès dans l’ensemble de portraits que lui a soumis l’artiste… Si le bonheur se laisse facilement reconnaître, il est plus difficile à trouver. Avec son projet Doomed Paradise, le photographe Tomas Wüthrich offre une vision absolument ambivalente du bonheur, résultat d’une immersion de cinq ans dans la tribu, de plus en plus menacée par la déforestation, où s’était réfugié l’activiste environnementaliste Bruno Manser. Imprimé sur du papier minéral et incluant des contes, des chants et des sons ambiants, le livre sert autant de mémoire à la tribu de son lieu de vie et de sa culture perdue, que d’une profonde réflexion sur le bonheur et le lointain.

C’est aussi une réflexion sur le proche et le lointain qu’entretient le studio de design crisp-id, comme le montre leur collection Tabletop Bistrobar pour le restaurant bernois Casino. Au lieu d’une vaisselle anonyme, le duo a créé une collection réduite et robuste, mais à l’usage versatile, basée sur la terre cuite du producteur le plus proche possible du restaurant. Comment le produit s’adapte-t-il à l’environnement? Peut-il réagir et servir au mieux avec le changement? C’est la question à laquelle répond le typographe David Massara avec son projet de recherche Ripley : Sa police de caractère variable intègre les informations des détecteurs de lumière omniprésents dans nos interfaces digitales afin d’optimiser la lisibilité à l’écran automatiquement. Plus avant, l’exploration de la dimension poétique de l’automatisation floute rapidement la limite entre art et design. Se trouve là le duo de designers d’AATB, qui d’une part invente le luminaire à dessiner Phasma à partir d’un module éléctronique, d’autre part équipe un bras robotique d’une lampe de poche pour récréer un cadran solaire intérieur.

Dans un genre plus discret mais tout aussi expérimental se trouve les Softspace de la designer textile Marie Schumann. Ni meubles ni luminaire, ses tissages suspendus cependant habite et transforme l’espace. Réalisés à la main selon une technique expérimentale sur des machines en Suisse et en Hollande, ses textiles combinent coton, polyester, fil Lurex, et plus récemment LEDs et fibres optiques. Le développement par les designers de techniques et d’outils propres se retrouvent aussi chez les graphistes d’Eurostandard. Leurs compétences combinées dans le graphisme et la programmation leurs permettent de développer des outils digitaux spécifiques à la commande, comme pour l’identité visuelle du festival versatile et polymorphe Les Urbaines, tout en étendant leur propre savoir-faire. La question de la durabilité occupe aussi le domaine de la mode, pour le label autant que ses produits. Le duo de Collective Swallow développe ainsi son propre rythme de lancement, voyant chaque série comme une extension d’un ensemble ouvert. Pour cela, le label se base sur un concept narratif fort, transformer une expérience gustative et sociale en série de vêtements – impliquant un grand soin dans la matérialité et une fine dose d’humour.

Ces qualités se retrouvent dans les illustrations psychédélique de Luca Schenardi, que ce soit pour les journaux, les lieux de culture ou la musique. Avec la spontanéité du dessin mêlée au machinique du digital, Schenardi donne un accès sensible, une compréhension intime des sujets illustrés. Cette compréhension de son sujet se trouve d’une toute autre manière chez la photographe et directrice artistique Laurence Kubski. À partir de ses immersions dans les rapports entre humains et animaux, Kubski reconstruit avec une forme d’empathie distante un univers autrement inaccessible. Au lieu de nous montrer un univers, Kubski fait le choix d’interprêter une culture. Ce désir d’une mise en scène d’une culture se retrouve dans les collections du label de mode After Work Studio. Urbaines, insolentes, et cependant sans le moindre compromis sur la qualité, les collections d’AWS semble venir du New York City de demain. Également connue pour ces mises en scène décalées pour les plus grands magazines de mode, la photographe Mathilde Agius s’engage dans une nouvelle voie plus personnelle, faisant le portrait des nuits de Shanghai à travers ses amies DJs. Basée à Genève, la jeune designer de mode Lora Sonney explore une autre approche pour une culture urbaine et féminine. S’inspirant de l’ambiance moite et fraternelle des vestiaires de foot, elle compose une collection féminine de sportswear souple et énergique, tout en développant une maille textile expérimentale pour l’extérieur. Toujours pour l’espace extérieur, le designer industriel Michel Charlot a développé une toute autre maille. Avec le banc Biennale Bench, commandé par la Biennale de Design de Fiskars, le designer a posé la base en cours de développement avec Burri pour un système de banc urbain modulaire en maille métallique quasi transparent. Egalement inspiré par l’un des (encore) principaux acteurs de l’espace urbain, la voiture, le designer de mode Thomas Clément déplace l’auto à même la peau. Combinant dentelles et tartan avec des résines synthétiques et des bas, le designer signale le passage vers une corporéité urbaine à venir.

Comment un territoire s’incarne dans le corps et la langue des habitants se trouve au coeur du projet Medicine Tree du photographe Lucas Olivet. Le titre est tiré d’une métaphore d’un habitant rencontré au cours de sa recherche à propos de l’épinette noire et résineuse qui pousse près de sa caravane délabrée: «Je n’ai jamais vu un arbre faire autant de médecine. Peut-être pleure-t-il pour tout le poison qu’il y a ici.» Comme des extensions de nos sens, ces reportages nous aide à créer un sens pour notre monde décidément globalisé. Allant dans ce sens, rapportant les facettes les plus étranges ou troublantes de notre planète, le magazine Reportagen travaille avec l’illustratrice Lina Müller, dont les images capturent l’esprit du lecteur comme des rébus qui s’inscrivent dans les plis de la mémoire. Egalement intrigué par le rapport entre la mémoire et le corps, le designer de mode Luca Xavier Tanner lance sa carrière une collection de vêtements upcyclés unisexes. Provenant de sa garderobe ou celle de ses ami-es, Tanner y insère des plis et des volants, recomposant les contours du corps habillés.

Cet art de la composition le photographe Mathias Renner la pousse à l’extrême avec ses natures mortes. Ses images assemblants les objets les plus communs fonctionnent comme des idéogrammes défiant notre imaginaire. L’urgence d’aujourd’hui réside peut-être bien dans ce défi, cette ouverture de l’imaginaire maintenant. C’est ce que semble impliquer les étranges cabanes du designer Stéphane Barbier Bouvet: Il s’agit de rester à l’affût des possibles présents tout en s’ouvrant aux fonctions à venir, de faire avec ce qui existe, et de sortir de la logique du projet remettant toujours à demain les transformations nécessaires du monde contemporain. C’est aussi le pas que la designer Martina Huynh entreprend avec son basicincomecafe.com, dans lequel deux modèles de revenu universel sont directement mis en pratique et discuté collectivement. Parallèlement, le photographe Marwan Bassiouni rend tangible à quel point les différentes «conceptions du monde» sont enchevêtrées dans le monde présent. Ses New Dutch Views montrant le paysage néerlandais à travers les fenêtres de mosquées indiquent à quel point l’hétérogénéité culturelle compose notre environnement quotidien. Il n’y a pas l’un sans l’autre, la cohabitation nécessite des contrastes et du jeu, un peu comme les découpages de l’illustratrice Nadine Spengler. Le photographe Roger Eberhard rend compte d’autres découpages, qui, non sans ironie, n’ont eux pas résisté au passage de l’histoire. Human Territoriality présente 42 paysages de frontières qui n’existent plus aujourd’hui.

Simplifier sans perdre de substance est une tâche ingrate qu’embrassent cependant avec enthousiasme nombre de designers. Les dessins naïfs et colorés de l’illustrateur Luigi Olivadoti rendent accessibles des sujets de société délicats, tandis que le graphiste Roger Conscience développe depuis quinze ans l’art des diagrammes et des tableaux, donnant non sans humour une forme visuelle aux données les plus complexes. Le dépliage par le design est aussi au coeur du travail Cypriot Sketch de la graphiste Clio Hadjigeorgiou. Sous la forme d’un livre, la designer donne à parcourir de manière empirique la construction d’une culture cypriote à travers les appropriations et transformations faites sur les nombreuses cultures qui ont croisé l’île. C’est aussi l’entreprise à l’échelle globale de l’équipe de recherche derrière Migrant Journal, qui en six cahiers soigneusement réalisés rendent compte d’une planète essentiellement définie par la circulation.

is a designer based in Lausanne. Beside his independent curatorial and exhibition design practice he collaboratively develops installations and publications. He is also co-founder of iiode, a company for lighting technologies and responsive environments, partner of a carpentry specialized in digital fabrication, as well as research assistant in the architecture department of EPFL in Lausanne.

Yves Mettler’s work aim at building a sense for today’s global urbanisation processes. His work ranges from interventions in the public space and sound installations to publications. The works present a narrative fabric, giving the urban environment a polyphonic, emotional, and often humourous, expression. Since 2003 Mettler develops a research & art practice around urban places called “Europe square”, cultivating the spaces between urban reality and symbolic values. His works have been shown at Galerie Georg Kargl, Vienna (2018), Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin (2017), Bozar, Brussels (2016), Musée Cantonal des Beaux-arts, Lausanne (2011), Bawag Contemporary, Vienna (2009). In 2010, he participated in Bruno Latour’s Art and Politics Pilot project at Sciences-Po. He holds an MFA from the Vienna Art Academy and an MA in Art Theory and Language, EHESS, Paris.